My initial answer? Defence takes priority. Another may, legitimately, say “Striking takes priority”. The truth, in my opinion, lies somewhere on a spectrum of possible genuine answers, with folks positioning themselves based on their combative preferences. And this, for me is where the discussion gets messy.

For this, I will make the case for “Striking takes priority” first, in an effort to ‘steelman’ the argument opposing my initial position, then highlight the reasons why I take defence as the combative priority and then finally, where I think both arguments have issues at their extremes.

Striking as a priority.

As an instructor of combatives once told me and has stuck with me, “Self-defence is all well and good, but it’s better to get your defence in first!” Terry Pratchett uses a similar line in his City Watch series, for much the same reason.

Being the aggressor has an entire host of advantages. You set the pace of combat, you dictate the opening moves of the engagement and you can put on significant pressure if you can mask your movements and intent within your setup, for example the concept of High/Low Stimuli in particular is useful here.

Chiefly though, you have the first play. It is likely that an opponent may simply fail in their defence and that first hit is yours. Similarly, if you play for speed and explosive power, even if that hit doesn’t connect, the speed of it may shock your opponent and put them on the back foot mentally, as well as in the flow of the fight itself, leading to mistakes that can be capitalised upon.

This is doubly true when a competitive ruleset means that a match will be halted at the “first touch”. In these situations, defending as a priority simply limits your potential scoring actions and relies on your skill to deny the opponent points, rather than making actions that merit chances of scoring. This may be dependent upon the competitive practice, but even in situations where “first touch” isn’t the deciding factor, for example Queensbury rules in boxing, defences alone don’t merit points, strikes do.

In martial practices where injuries can result from strikes, these attacks can have a debilitating effect upon the opponent, stunning and disorientating them will limit their reaction time. Similarly cuts and stabs can lead to a lot of pain and even limitations in range of motion, making subsequent defences even harder to execute. Thus striking first can leverage a significant advantage. When you factor in the ability to displace your body within your attacks, positioning yourself such that a simple returning strike in the same tempo will have less chance of hitting, striking first becomes a useful training mantra and one to consider within your training skillset.

Defence as a priority.

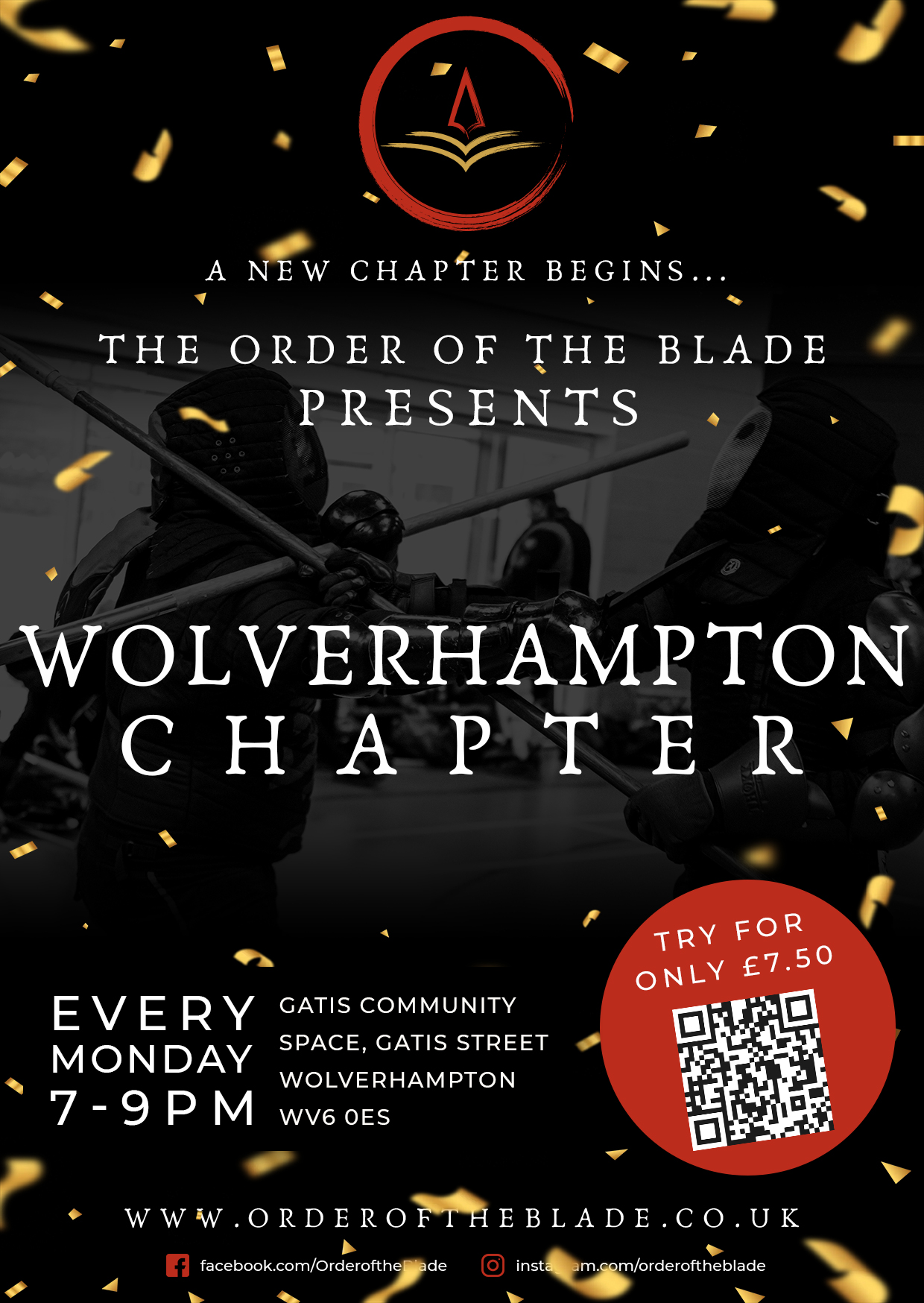

Now, I’ll preface this section by stating that I have given in all seriousness the above advice to students within the Chapter training sessions. There are perfectly valid situations where making the first action is entirely appropriate, and personally, I often find myself in the seat of an aggressor, despite a defensive intent and priority in my personal style and approach. This is for one simple reason:

By striking first, I limit my opponent’s opportunities and thus narrow down my own defensive considerations.

This may sound like advocacy for ‘striking as priority’, however it does not factor in for an artefact that is common, particularly against skilled opponents – the ability of the opponent to handle the first strike, and having pre-prepared and drilled counters to standard attacks.

With an opponent able to issue such responses by reflex and with a measure of the competence found amongst higher level practitioners, you are left with two principal routes to handle this. The first is to provide a more complex attack method to increase the pressure, whilst the second is to work on a defensive response to the counters.

Within a ‘striking as priority’ method, complex attack methods will be the obvious choice, single-time feints, winding strikes against the defensive response, even double action strikes where the first attack is to setup the opponent for a follow up move. Now although all of these can work, the key word here is ‘can’.

It’s not guaranteed that the opponent will respond in a way that’s conducive to our intentions. They may issue their own attack in tempo and fail to defend themselves adequately, which renders our more complex attack method moot and we may get hit. In a similar vein, dedicating more to a complex attack method will necessitate an increased level of focus on that attack, lowering our capacity to respond to an opponent’s imposition or adverse action.

Complex attack methods can work, but rely upon expected actions from our opponent. I have rarely found that opponents are particularly co-operative in a contest. I consider this an over-extension.

This is why I prefer the ‘defence as priority’ method of combat. Sure, I can open out with a basic sequence of cuts which can either land or be defended as the opponent’s skill dictates, but I am not committing a significant mental load or physical commitment to this, they are just initial openings. Should they land, I will take that win with pleasure, but by and large, particularly against skilled and practiced opponents, they will have a response waiting.

Being able to break out of an attack pattern and switch to defence against such countering responses from the opponent keeps you safe. Sure, you aren’t going to land hits in that action, but you are able to get a read on your opponent and their tactics in that brief exchange. Your defence doesn’t even need to be bladework, though it often is in my case. Evasive footwork can serve as a defence method all of its own, and while it may bring you out of effective range on your opponent, it could force them to over-commit.

For my practice, the defensive response proves itself in a topic of particular interest, battlefield combat. I may have locked down one opponent with my opening salvo of attacks, but if another combatant is free to issue attacks against me, I would leave that flank exposed if I did not break off and deal with the incoming threat. Sure, I also alleviate the pressure I applied to my primary target, but I remain combatively viable. The initial opponent may see the secondary attack and choose to draw me in, bunkering down while their ally drives home the winning shot. If I disengage and turn to meet the new threat, I can answer it with

defensive responses and keep the battle going.

This defensive response also paves the way for counter-offensive methods of my own, exploiting weaknesses in my opponent’s actions, particularly relevant if the opponent has fired off their responses by rote, or under stress which may lead to errors. If by rote, and I recognise the move being used, I have the space to answer with my own counters. If an error is presented, then I can capitalise upon this error as per my styles approach. Some will jump on it and strike against the weakness, where others will allow it to happen and capitalise in the after-action.

Even in duelling, it may be a reasonable strategy to pile on the pressure if your opponent’s defensive efforts are becoming frantic, but it’s just as likely that they will launch an attack to alleviate said pressure. Rather than go more complex in attack, I typically maintain the offensive cadence and pattern and allow for defensive breakouts to handle any incoming threat.

Limits of each method.

I have already outlined some pitfalls within what can be useful approach to combat, but in practice both approaches have issues. If you attack without thought to defence, then – even if you land a strike – you will end up getting hit. If you defend without thought to counter attack, then you will end up not being able to hit your opponent, and potentially getting hit yourself.

Both extremes are untenable to a practical fighter of any style. There could be valid reasons why you may fail on both ends of this. If you cannot see a valid counter-offensive method, then you may bunker down and become overwhelmed by the opponent’s attacks. This is common when new fighters face more experienced opponents. Equally, if you attack without regard for the opponent’s actions against you, you’ll end up doubling.

Both can be seen as errors in judgement in the moment. In practice, the needs of the moment will dictate what is required from each combatant. What may work for one fighter, who may be more athletic and with quicker reactions, may not work for another, and the methods they use will dictate which options are valid.

Personally I don’t see the trade as worthwhile to score a shot at the expense of taking a hit, as even a minor cut to the arm can be dangerous in its own right, hence why I prefer the defensive priority. Combatants with different skillsets may view it differently. The best way to discover what works for your style, instincts and skillset is to fight and spar with opponents of different opinion and training, and compare where your technique falls short and where

theirs works.

Only by training with each other can technique be elevated.