Let us first set out why this is important. For those of us with significant martial arts experience, there will naturally be those who rise to the top of the club hierarchy and, if the club is tournament focused, this individual could get an undue amount of attention by the instructor and by the group in general as the training is turned to support this high performer, typically at the detriment of the rest of the group. Further to this, in groups where clear divides in hierarchy are present and there is little mixing between the ranks and grades, this can create micro-cultures within the class that can be damaging if not correctly managed. Where veterans do not train regularly with novices, the divide can cause resentment and even turn away newcomers to the group.

Practically every person who walks in through the door has the potential to become a valuable sparring partner and addition to the group, but the culture must be inviting enough and welcoming to encourage these newcomers to become invested in the sport, otherwise growth of the club is a tricky task to accomplish. Therefore, the club culture must be set out and maintained by the leadership of the group and understood by its membership.

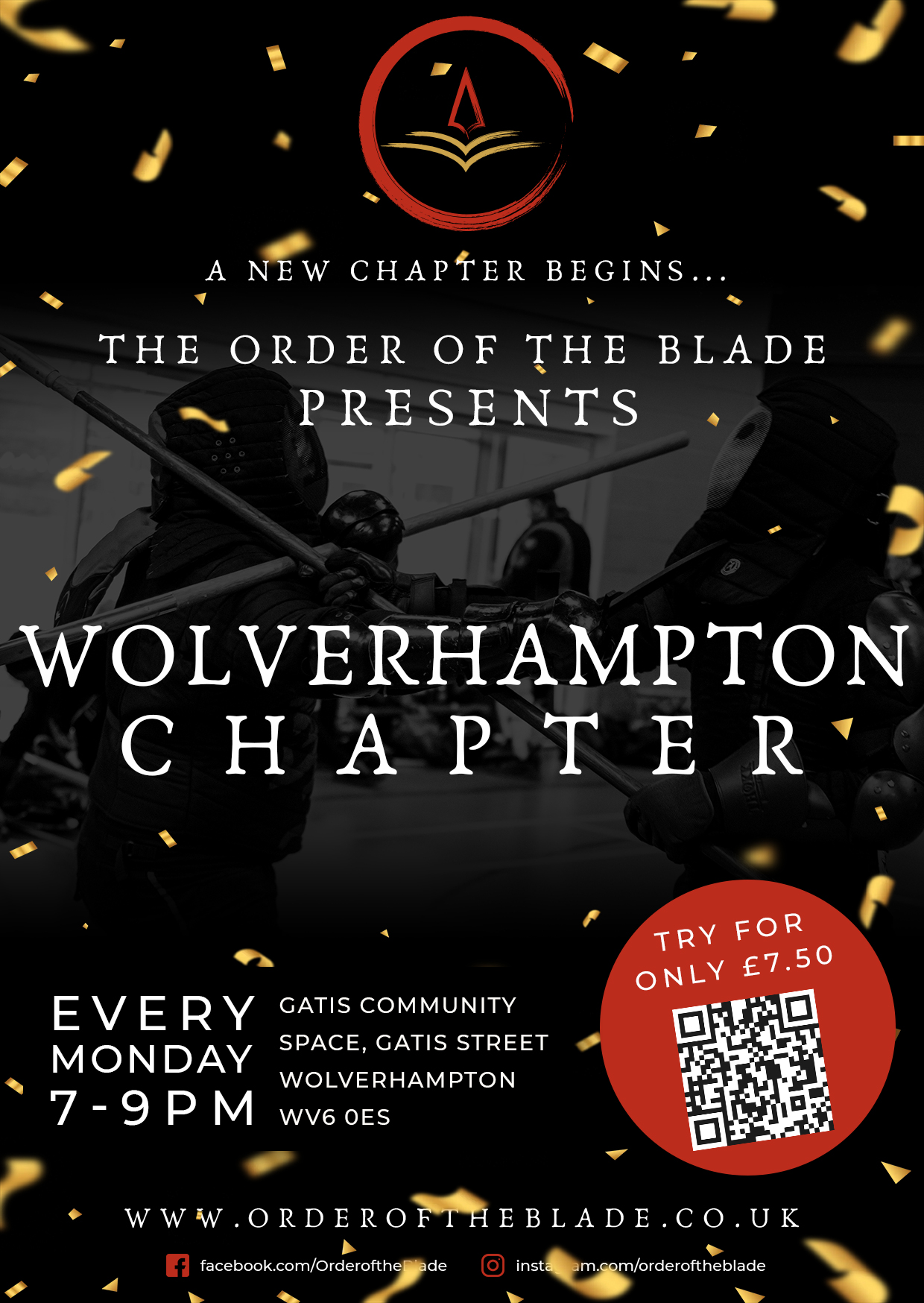

Within the Order, we have multiple levels of training, Chapter sessions for the bulk of our training, focused on the Primus Syllabus, augmented by private training with instructors to focus on particular elements and then enhanced with the ‘Masterclass’ sessions to dive deep into the theory to give the more advanced members chance to expand their practice and fine-tune their skill sets. Even the Musters serve a purpose in providing a target-rich environment to test your skills against a range of opponents. The training culture within the Order remains the same even between the different training sessions.

This culture is encapsulated by the term “Selfish-Altruism”, itself a paradox, but is a relatively simple premise. Utilise the selfish desire to get better in combat to benefit the group as a whole. The main reason anyone takes up this sport is to better themselves in combat and learn the arts of combat, rarely does anyone join with the intention of supporting a local group for its own benefit. As such, we have to use this drive and make it beneficial to the group culture as a whole.

“I want to get better at armed combat. In order to improve, I will need good opponents who can test me.

If I cannot find good opponents in my group, I help others to improve so that they provide me a better challenge.

Once I have good opponents, I can improve.”

This phrase by and large sets out the Orders’ driving culture. For most of our members, there is a real drive to push their skills and abilities with their chosen weapons to the apex of their potential. By this logic, we can utilise that singular focus to encourage co-operation between competing opponents. Let’s break down each statement in turn and go deeper into each premise and how it works in practice.

“I want to get better at armed combat. In order to improve, I will need good opponents who can test me.”

This statement is central to an individuals’ performance and development. In competitive practice, we are seeking to find issues with our method and rely on our opponents to find gaps in our defences and methods so we can improve them through study and training. Without a skilled opponent to find these errors in our form, we are reliant on the training method to provide all of our feedback and development. A phrase often touted amongst those who train competitively, “No matter how good the teacher is, sparring is a better teacher”. While this is largely true, sparring will highlight your gaps in knowledge or skill better than an instructor will, yet the job of the teacher is to show you how to fill those gaps and build effective technique for handling those situations better.

Reality is that a mix of both good tuition and practical experience will make for an informed and capable student. This feedback requires that those you train with are familiar with your approach and able to exploit any weaknesses they can find. A skilled opponent is one of the best training partners as they can observe your form frequently and keep you on point. In an ideal environment, such opponents will be readily available and ready to offer you the chance to learn, yet this is not always the case.

“… If I cannot find good opponents in my group, I help others to improve so that they provide me a better challenge.

Once I have good opponents, I can improve.”

This second part is where the culture is defined. Within the Order, we are a group that frequently works in competitive practice and as such, cliques are easily formed amongst those who frequently train together, yet it is important to bring other members into this practice as much as possible. Sometimes, these members need a bit of training and conditioning to adjust to the level of practice and to those they will be fighting regularly. One thing we try to remind our veterans is that its just as important to be tested by someone who is unfamiliar with your technique, so that you can see if your basics hold up to a thorough testing. Sometimes, an enthusiastic novice is the best analogue for this practice.

Through training with a more experienced opponent, that novice will develop and adapt quickly and learn the nuances of your approach the more you spar them. As they develop and learn, the naturally competitive practice will drive them to find gaps in your technique. This will achieve the objective of reinforcing their learning and understanding of their chosen system, but also provide you with another person able to test you in the competitive practice.

If you are finding amongst your core of sparring partners that they are struggling to overcome your form, this may be momentarily exhilarating, but consider the longevity of your practice. If you take that time to teach your fellows the techniques and methods you are using, you will help them improve, either by adopting the new method, or getting better insight into your approach and potentially finding a method of countering the system.

In either case, taking the chance to demonstrate and help others understand the route to your success will not only raise the standard of the group, but also give you a platform for further improvement. Moment by moment victories can be a great feeling, yet there is further potential to be found working as a group to push each other higher.

Through this imperative, the Order can push each of its members to the heights of their individual potential, yet still benefit the group. A duality of imperatives achieved by understanding the value of a good opponent and sparring partner. This theory is closely linked to the understanding of competitive game theory, where the aim is to create an equilibrium between the opposing forces, yet rather than each person being in direct competition, where the outcome is zero-sum, both parties can benefit from the advancement and momentary rise of another within the group. The aim must be in that person either disseminating their skillsets out to their training partners, or by those in competitive practice developing solutions to overcome the challenge.

By either method, the standard of the group rises. So long as novices are bought up to the standard in a healthy manner and the instructors focus on developing those coming into the system effectively to handle the training environment, then the strength of the group improves by having another point of view added to the mix.

Not every person will end up being so altruistic and enjoy that feeling of superiority in the moment. Their success is equally something that must be celebrated as they will have put significant work into developing themselves to this point. This is where it is important for the group to put them under pressure and seek to overcome them in competitive practice so that the group can learn and adapt to the new paradigm. So long as this practice remains within the bounds of good sportsmanship and the understanding that everyone is there to improve their skills and the practice of sparring remains competitive, then the notion of ‘selfish-altruism’ can serve to drive the whole group to greater performance.

When either joining a new group, or even setting one up, it is important to consider the culture you are establishing within the group. What are its ultimate objectives? Who is likely to join? How do you retain new members? How do you inspire veterans to higher levels of practice? What are the common elements which bind the group together and encourage that co-operation and competitive practice between them? Without some sort of common understanding, it can be difficult to develop a group and grow it effectively.

Richard Hughes